To Tell a Proper Story In Celebration of Alice Munro

Ashley Wurzbacher

Nov 15, 2013

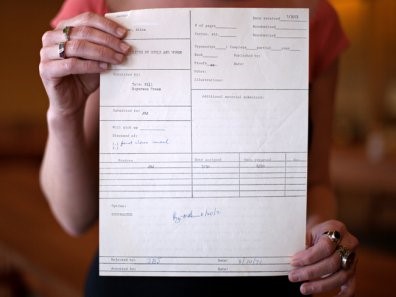

By now many people might have put down their champagne glasses after toasting to Alice Munro, celebrating her work and her legacy in the wake of her recent receipt of the Nobel Prize. But I’m still riding around on a little cloud of joy, revisiting her work and contemplating what it means to me—as a woman, as someone who loves and works in the short form, and as a writer and reader in general. Recently an article in The Daily Texan announced the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin’s possession of several rejection letters sent from Knopf to Ms. Munro. In the article Ann Cvetkovich, a professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies, speculates that Munro’s early work was rejected primarily due to her nationality, explaining that “so often, good writers are not always recognized because they fall off the radar due to their gender, sexuality, race or in this case, their national background.” Having not seen the letters myself, I can’t speak for the editors who first rejected Munro’s work, and while her national background may certainly have been a factor, I’d hesitate to assert with any certainty that it was the primary one. I find it even more difficult to imagine why, even now, I still hear, and read of, writers asserting that Munro’s work is “boring” or “overrated” (I’ll refer you to Derek Askey’s post over at the Colorado Review’s blog for an overview of Bret Easton Ellis’s recent Munro-bashing). Granted, they’re the minority; I feel the vast majority of the literary community rejoicing with me in Munro’s victory, and it’s fabulous.

But if I use my imagination and try to do my own speculating on what may have driven—and may still drive—certain readers away from Munro’s work, my feeling is that their unappreciation stems not simply from her nationality or her femininity, but from the femininity of her prose itself, and its domestic, internal subject matter. Moreover, it might be because of the way that she breaks every rule of a “proper story,” experimenting with point of view, examining the limitations of narrative, playing with time. I’ll examine two of my favorite Munro stories—“The Ottawa Valley” (1974) and “Friend of My Youth” (1990)—for a few examples of the way Munro’s work challenges the reader. The narrator of “The Ottawa Valley” remembers a trip she took with her mother, who has since died of Parkinson’s disease, back to her childhood home. The story offers little in terms of plot; its narrator recalls moments (like a memory of her mother giving her a safety pin during a church service), snippets of a narrative, but no single, linear “arc” of obvious significance. The story maintains tension not by prompting us to wonder what will happen next, but by commenting on its own metafictional work, and the way that that work must inevitably fail—the narrator is unable to capture, through narrative, the essence of her mother, and this failure is the heart of the story. The epiphany is that there is no epiphany—or at least, not enough of an epiphany to provide catharsis to the narrator. The narrator comments on the structure and conventions of her own story, observing where and how perhaps it “ought” to have ended and critiquing her own (in)ability to capture her mother:

For 50 years, WWF has been protecting the future of nature. The world’s leading conservation organization, WWF works in 100 countries and is supported by 1.2 million members in the United States and close to 5 million globally. If I had been making a proper story out of this, I would have ended it, I think,with my mother not answering and going ahead of me across the pasture. That would have done. I didn’t stop there, I suppose, because I wanted to find out more, remember more. I wanted to bring back all I could. Now I look at what I have done and it is like a series of snapshots, like the brownish snapshots with fancy borders that my parents’ old camera used to take.This is the story—the ending—that might have been; but it isn’t our story. So what of our story? Is it not a “proper story”? What is a “proper story”? What is the norm against which this narrator—and Munro herself—is positioning herself?

|

The problem, the only problem, is my mother. And she is the one of course that I am trying to get; it is to reach her that this whole journey has been undertaken. With what purpose? To mark her off, to describe, to illumine, to celebrate, to get rid, of her; and it did not work, for she looms too close, just as she always did….and I could go on, and on, applying what skills I have, using what tricks I know, and it would always be the same.Here writing is the mechanism not only for conversations and connections between generations, between the sexes, between women across differences and distances, or between living and dead. It is also a mechanism for exorcism, or at least its attempt; it gives access to memories and, in the act of relating them, attempts to free the writer from them. It lets us reach for understanding, but that reaching is all there is—we can never completely grasp it. The spirit of the mother can neither be expressed nor exorcised; she can only haunt this narrator and her narrative, give us a piece of a bygone generation, a snapshot, to do with what we will. (Yes, men’s postmodern writing performs many of these same moves—rejecting the notion of absolute truth, providing metafictional commentary on itself and on the limitations of language—but Munro’s work differs from theirs in several key ways: its quiet, contemplative tone; its focus on domestic subjects and settings and on relationships between women; the way that it is always subtle, never flashy or demonstrative in its theorizing or its rule-breaking; the way she examines, again and again, not only the concept of storytelling in general, but also the way that storytelling affects women’s gender identities. Due to space constraints, I won’t belabor this point.) “Friend of My Youth” introduces us to a similar narrator in a similar situation. Her mother, too, has died of what seems to have been Parkinson’s. This narrator tells the story of Flora, a woman with whom her mother boarded many years in the past when she was a schoolteacher in the Ottawa Valley preparing to marry. The narrator recalls and recasts her mother’s stories of Flora, resisting her mother’s interpretation of her and her story, and imagining telling an alternative version in which Flora is a villain rather than a dignified, long-suffering saint. Through telling and re-telling the story of Flora, the narrator attempts to come to terms with her relationship with her mother, their many differences, and her mother’s death.

|

Comments (0)

Add a Comment