Bad Poet, No Biscuit

Kimberly Bruss

Sep 22, 2012

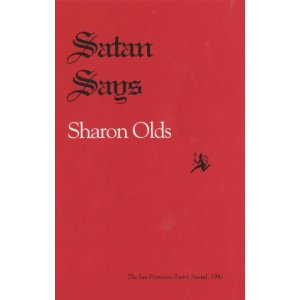

I have a friend in the poetry program here who swears up and down, side to side, that he hates poetry. I'm not talking about the kind of hatred that accompanies respect for but frustration with a body of artwork--that is, I hate opera because I do not understand it and it makes me feel like the country bumpkin I most likely am. No, my friend has a good understanding of the workings of a poem and poetry in general--and he seems to hate it all the same. This whole I-have-a-friend-of-a-friend thing isn't meant to be a mask--I actually do have a poet buddy who claims to hate poetry. But I suppose I should come clean: more often than not, I hate poetry too. I know this is not wise, but I can't help myself. Sometimes I read Emily Dickinson and I want to pull my hair out. The Waste Land was a waste of my time. Wordsworth and Coleridge are, in my opinion, drug-free cures to insomnia. I want to like these poets because that would satisfy the bourgeois student part of my heart, but I just can't bring myself to be moved by their work. And, more importantly, I don't think it is my job to work at liking these artists and the myriad of others that I haven't listed. Isn't that what art is supposed to do? Isn't art's responsibility to pull something out of its audience? Sometimes when I read poems, I feel that I am working harder than the artist. And that pisses me off. This semester, I have the opportunity to teach an Introduction to Poetry class. I was told that teaching these classes is exciting because your students actually want to be there, as opposed to the university-mandated comp classes that everyone is forced to take. This is almost wholly incorrect. Out of my 30 students, about 6 have some affection for poetry. The rest of them don't care a stitch for poetry, simply biding their time in my class in hopes of getting that final humanities credit. I ask them, "Why do you dislike poetry?" I get several answers, all of which stem from the same root--the poetry we learned in school, the poetry that is being taught as representative of the genre as a whole is of the ambiguous, riddling variety. Yes, in school we all read "Dover Beach." Yes, we all read "Annabel Lee," and "Because I could not stop for Death," and "The Tyger." And they were all riddles--things we had to decode to get to the "real meaning" of the poem. By and large, this type of poetry doesn't excite me. I want art to teach me about life, not to provide some exercise, some opportunity to practice my critical thinking skills. Because, soon enough, that's all poetry becomes--a game to play, a riddle to decode. It becomes mechanical and cold, like it has for some of my students. I love Sharon Olds. She was my gateway poet, the person who made me care about poetry. I remember reading Satan Says and feeling so close to her speaker, like she had taken the words--not from my mouth, because they hadn't even formed there yet, but from somewhere deep within me. I'd like to thank Olds for her work, because I haven't felt that exhilarated about poetry since picking up her little red book. When I watch episodes of Intervention, which is frankly pretty often, I can understand when the addicts say their continued drug use is all in chase of that first high. I've been waiting a long time for something to get me as excited as Satan Says did. I've had to wade through a lot of muck without much reward.

My point is that I'm sick of the academy telling me what I should and should not like, and I'm sick of teaching my students--the majority of whom hate poetry, anyway--the so-called canon when I could be spending my time teaching them poetry that excites. I've told professors before that I enjoy about 10 percent of the poetry that I read. I thought this admission would be a nail in my coffin--proof that I didn't belong here in this wonderful program among these beautiful, poetry-loving people. But I've discovered that we all only like about a small portion of what we read. When I say I don't like Emily Dickinson, I'm not arguing that she has nothing to offer or that she shouldn't be taught. When I say I love Sharon Olds, I'm not arguing that she's the be-all, end-all or that everyone should count her as an influence. I'm asking that my love of her be respected, as well as my aversion to Dickinson.

It is difficult for people to accept that I'm not a fan of America's poetic mother; I've had many people try to reason with me, to convince me of her greatness: Her use of the dash is a way to maintain quatrains while still imposing a caesura that imitates a line break! "A narrow Fellow in the Grass" is brilliant because the poem's not really about the snake at all--it's about the unknown!

But there is no reasoning with taste. Dickinson does not move me. I don't care to figure out what she's trying to say. Does that make me a bad poet? Perhaps. Or perhaps there are dozens of poets out there, loathing Emily Dickinson in silence, waiting for someone else to say it first.

I love Sharon Olds. She was my gateway poet, the person who made me care about poetry. I remember reading Satan Says and feeling so close to her speaker, like she had taken the words--not from my mouth, because they hadn't even formed there yet, but from somewhere deep within me. I'd like to thank Olds for her work, because I haven't felt that exhilarated about poetry since picking up her little red book. When I watch episodes of Intervention, which is frankly pretty often, I can understand when the addicts say their continued drug use is all in chase of that first high. I've been waiting a long time for something to get me as excited as Satan Says did. I've had to wade through a lot of muck without much reward.

My point is that I'm sick of the academy telling me what I should and should not like, and I'm sick of teaching my students--the majority of whom hate poetry, anyway--the so-called canon when I could be spending my time teaching them poetry that excites. I've told professors before that I enjoy about 10 percent of the poetry that I read. I thought this admission would be a nail in my coffin--proof that I didn't belong here in this wonderful program among these beautiful, poetry-loving people. But I've discovered that we all only like about a small portion of what we read. When I say I don't like Emily Dickinson, I'm not arguing that she has nothing to offer or that she shouldn't be taught. When I say I love Sharon Olds, I'm not arguing that she's the be-all, end-all or that everyone should count her as an influence. I'm asking that my love of her be respected, as well as my aversion to Dickinson.

It is difficult for people to accept that I'm not a fan of America's poetic mother; I've had many people try to reason with me, to convince me of her greatness: Her use of the dash is a way to maintain quatrains while still imposing a caesura that imitates a line break! "A narrow Fellow in the Grass" is brilliant because the poem's not really about the snake at all--it's about the unknown!

But there is no reasoning with taste. Dickinson does not move me. I don't care to figure out what she's trying to say. Does that make me a bad poet? Perhaps. Or perhaps there are dozens of poets out there, loathing Emily Dickinson in silence, waiting for someone else to say it first.

Comments (7)

Sandy Longhorn:

Oct 12, 2012 at 05:14 PM

Wonderful post. I echo Brooke Passy's thanks for the honesty. As someone a decade out of my MFA program (oh my!) and a decade into teaching, I think it is important that we acknowledge the harm done by forcing the canon down the throats of students before they've encountered a "gateway poet," as you so wonderfully describe. Times change; the language changes. Yes, there is worth in studying the canon, but I've had much more success in working from the present backward than from the ancients onward. I think this is especially important in intro courses when we have an opportunity to show students the power of language. PS. I love Dickinson, but I certainly respect your preferences as well! It's a big ol' poetry world!

Brooke Passey:

Oct 12, 2012 at 04:31 PM

Thank you for being so honest! I loved this post because I have had so many of the same feelings about different areas of poetry and lit in general. I can appreciate all kinds of writing, but it doesn't mean that it all speaks to me. You've motivated me to own up to my taste, even if it's the minority at times. "Sometimes when I read poems, I feel that I am working harder than the artist. And that pisses me off." This made me laugh because I'm right there with you. Thank you for sharing!

Charles beardsmug:

Oct 12, 2012 at 10:39 PM

Kimberly, You ask that your love of Olds be respected, as well as you "aversion to Dickinson". Sure, I can respect your personal tastes. I like Mozart, you like Justin Bieber. No foul. But if you're teaching poetry to others at a university, or writing for a literary journal, I would expect a more... intellectually open approach? The fact that a certain poet 'excites' you, that you 'feel so close' to whomever you think Sharon Olds' "speaker" is in her poetry, means nothing. You can't simply displace the canon by saying, 'that's just my opinion' or 'de gustibus non est disputandum' (in matters of taste there is no disputing). You're not making an argument, you're not challenging your students or your readers. You're just stating your personal preferences. Who cares. So you don't 'get' The Waste Land, fine. But I don't think this is something to brag about. If you have a rigorous argument as to why The Waste Land is overrated, that's one thing--and you have your work cut out for you. But the mere fact that certain canonical texts do not 'excite' you or your friends or your freshman students -this does NOT give any significance or value to credence your point of view. No, it's not your job to "like" Coleridge, Wordsworth, Dickinson, or Eliot; but glibly dismissing these artists, saying things like "The Waste Land was a waste of my time" is nothing less than a pledge of allegiance to philistinism. Feel free to revel in your lack of appreciation. It's a free country, as they say. But you're teaching at a university? If you loathe the thought of practicing "critical thinking skills," then what are you teaching, other than your personal and very limited preferences? You say "I want art to teach me about life, not to provide some exercise, some opportunity to practice my critical thinking skills." By this same logic then, you prefer 'exciting' art that requires of its readers little or no critical thinking? But how can you learn "about life" or anything else for that matter without thinking critically? Osmosis? Perhaps what you're really saying is that you want to read poetry that tells you what you already know in a way that's familiar, poetry that makes you feel secure by not challenging your values and beliefs? Luckily, there is plenty of poetry out there that does this. It's called "bad poetry." Finally, I very much doubt that you are "working harder" than the poets you mention disliking: Coleridge, Wordsworth, Eliot, Dickinson. In, fact I'm convinced the opposite is true. Love, Emily Dickinson, et al

Olga Mexina:

Oct 13, 2012 at 03:37 PM

I completely agree with Emily Dickinson, et al. There are two things that worry me. The way you present yourself in a light you don't really want to be in and the fact that you are teaching poetry to undergrads with this attitude. Your job as an instructor is to teach the canon, because it develops and structures taste (you know, when you choose what you like and dislike). I understand your concern though, it's hard to teach something you don't understand. Poetry isn't here to serve anyone, it is actually vice versa. A utilitarian perspective is the worst thing that could happen to any art, especially poetry. You are screaming, Kim, but there are no words, just wails.

JSA Lowe:

Oct 13, 2012 at 04:56 PM

So I'm going to wade in here, at great length (be prepared!), in my guise as poet and teacher as much as Online Editor, and single out two aspects of these arguments that seem to me to be important and may be getting confused with one another. Or, perhaps they aren't and I just want to jump in! Because I love a good poetry scrap on a weekend morning. But the two aspects are, namely: 1) our personal aesthetic and its influences; and 2) our teaching of poetic craft and literature. I understand Ms. Mexina as saying that (to paraphrase Marianne Moore a bit) she, too, dislikes Emily Dickinson. But that she takes her personal taste as relatively unimportant to teaching; she believes we as teachers must serve a higher cause than our mere individual preferences. And I will admit that I had this response to some degree myself, as I laid out Ms. Bruss's piece, which I intuit she's deliberately written to be polemical and fiesty. (I also know her to be more of a Lady Gaga fan than a Justin Bieber one). (Full disclosure: I drank with both writers last night, and consider them friends as well as colleagues; and, I wrote one of my master's theses on Dickinson. Even as I type this working on an academic paper on her inestimable influence on contemporary poets such as Karen Volkman and Mary Ruefle, among others.) Again, I think where the questions become interesting and/or divisive for me are along the two lines already mentioned: personal poetic taste versus passing along some knowledge or discourse which the community of all writers living and dead has anointed as canonical. As far as the first, I'm personally upset-verging-on-enraged that Ms. Bruss has had such an inadequate education. Bear with me. When I encounter students who hate a particular poet of name/note, I invariably discover that's because they were taught that poet very poorly. (Cf. Shakespeare-hating undergrads who have never actually attended a performance or read the play aloud, at pace, unencumbered by some kind of ugly, unwieldy glossary. Who mistakenly believe they need Shakespeare's English to be "translated" for them. Put away your dictionaries and study guides, high school teachers! Throw them straight into the deep end of a play; I promise they will swim, not drown!) So transitioning a poetry-ardent student clutching her copy of _Satan Says_ into a realm of more challenging work, into loving poets who require some unpacking and some instruction as to how to read them--well, for starters, I certainly wouldn't plunk Wordsworth in front of such a reader (Wordworth himself famous for wanting poets to write in plain language, of course--oddly enough, for someone who then bursts out into the _Prelude_). But Coleridge's unfinished creepy ersatz-lesbian vampire epic "Christabel"? Absolutely. Not Blake's "Tyger," perhaps, but what about his proverbs of heaven & hell? We must be alert enough to offer our students the shiniest red apples, the most tempting lures into (out of?) paradise. And then, once we've earned their trust, how about "He fumbles at your Soul--" or "I got so I could take his name"½those are among the Dickinsonian gateway drug-poems, as far as I'm concerned. My late Russian professor said it this way: some books are like stepping onto a ladder. And some are like stepping into a ditch. If I were trying to transition young poets (as I often am) from (more random names) Billy Collins and Olena Kalytiak Davis to Wallace Stevens or Lucie Brock-Broido, there are a whole set of techniques to get them to want to put in the overtime that those poems are going to require of them. Here I think of Dana Levin quoting Wallace Stevens: "A poem has to resist the intelligence almost successfully." The key word, Levin says, is "almost." Or Alberto Ríos, noting that the poet has to be doing 51 percent of the work for the reader to want to do her 49 percent. Then, as far as personal taste--we all know that the canon of American contemporary poetry is broad now, and includes Lyn Hejinian and Fanny Howe and Anne Waldman as much as Galway Kinnell or Donald Hall or WS Merwin. (NB that all examples are completely random and extracted from an undercaffeinated Saturday morning brain.) We are blessed with profligacy: the post-avant, the skittery poem of our moment, and much-maligned quietism (which is often pretty noisy). The time is long past for the flarfernuttier to lie down with the iamb; and I think for the most part, the beauty of American contemporary poetry is that we are able to do this with such wild success. Poets don't break out into fisticuffs during AWP (about poetic schools, anyway--maybe there are fistfights about other things, I don't know); and poets of all stripes and tribes can now get tenure. Ms. Bruss will find colleagues in her life (e.g., Ms. Mexina!) who also dislike Dickinson. I'm personally sad that she's denied the pleasure of hearing Emily's angry, ghoulish, lovewracked, mordant, dry-writted, hilarious voice in her head--but for my money that's because she's not heard the right poems at the right moment. Finally: Should Ms. Bruss teach Dickinson? Not if she hates her. I was a Dickinson indifferent myself, despite attending her alma mater, Mount Holyoke College, until I read a notoriously non-scholarly, in fact highly trashy essay by Camile Paglia (from _Sexual Personae_) which places Dickinson firmly on the side of Satan (along with poor Milton). Paglia reads Dickinson as a decadent, as thoroughly late Victorian and obsessed with St. Sebastianesque tortures of the body, metaphoric for mental and romantic anguish. This essay led me to Susan Howe and Heather McHugh's work on Dickinson, as well as Brock-Broido's controversial _Master Letters_ (which Ms. Bruss would love, I think) and thence eventually to some really first-rate scholarship. And these studies have also led me to be unable to read most Dickinson (like Tsvetaeva, like Hopkins) without weeping, because through those scorching poems I feel a skin's-breadth away from her, over the separating century-and-a-half between us. In short, I'm glad Ms. Bruss wrote this post, and that we published it, to start and continue the endlessly looping polylogue about (to quote Chris Kraus's _I Love Dick_) WHO GETS TO SPEAK AND WHY. If you're reading, and you have a thought, please add your comment! And thanks to everyone for playing so nicely--

JSA Lowe:

Oct 13, 2012 at 05:11 PM

Oh, and one more: "I cannot live with You - / It would be Life - " ½I defy anyone with half a soul, anyone who's yearned unrequitedly and been torn away from her beloved, to read this aloud, excruciatingly slowly, and not come *completely apart* during the last stanza. Dickinsonian last stanzas often seem like a conceptual or metaphysical puzzle to be learnt, at first, it's true. But I say just get married and then divorce, and those last stanzas will melt, unravelled by the solvent of pure unadulterated pain.

sophie klahr:

Oct 14, 2012 at 09:37 PM

I'm not going to weigh in too much here, but anyone engaged in this conversation may also be interested in an article Dorthea Laskey recently wrote for The Atlantic : http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/10/what-poetry-teaches-us-about-the-power-of-persuasion/263551/

Add a Comment